Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.

Romans 12:2 (ESV)

If practice makes perfect, what thoughts have you perfected by repeating them to yourself constantly? These are becoming your automatic thought patterns.

In the brain, renewing your mind literally means creating new, stronger neural pathways. This process is called neuroplasticity. You can think of it as trying to pave a new path through solid ground. The more you tread through this new path and create deeper tracks, the easier it will become to identify and walk down that path. Like building muscle, the more we strengthen certain pathways in the brain through practice, the easier it is to access those pathways.

In that same light, as we adapt to practicing healthier ways of thinking, new thought patterns can become a more consistent way of life for us.

Another of the beautiful complexities that is woven into the human mind is this superpower called metacognition. Metacognition is your ability to think about your thoughts. This means that you can separate yourself long enough to examine your own thoughts. And if you can think outside of your thoughts, this is proof that you are not your thoughts.

Just because a thought exists doesn’t automatically make it true. At any moment, you have the ability to take a step back and choose between which thoughts you will align yourself with and which you’ll reject. It’s this very process of metacognition that allows us to “take every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5 ESV).

Isaiah 26:3 reminds us that “[God] will keep in perfect peace those whose minds are steadfast, because they trust in [Him].

How you feel about yourself or your circumstance today doesn’t change God’s call over your life. If a thought doesn’t align with who God created you to be — loved, forgiven, redeemed, secure, full of purpose, made for good works — then it is the thought that is flawed. It is the thought that needs to be changed and brought into alignment with the truth that never changed.

And now, dear brothers and sisters, one final thing. Fix your thoughts on what is true, and honorable, and right, and pure, and lovely, and admirable. Think about things that are excellent and worthy of praise.

Philippians 4:8 NLT

The Bible says that your body is a temple, but have you considered your mind as a part of this temple? How would your relationship with your thoughts change if you truly saw your mind as a temple — a sacred space worthy of intentional care, nurturance, and surrender?

You take your mind with you everywhere you go. How you interpret and respond to the people, events, and interactions around you is translated through your mind. This is why our thought life is worth paying attention to. But the health of our minds is also made up of what we’re feeding it.

Reflect on what has been allowed constant access to your mind that may have contributed to your feelings and attitudes this week: whether that positively or negatively impacted you, or simply drained you. And give yourself grace. It’s natural to live on autopilot, especially when life feels overwhelming.

Use this moment to reclaim your mind and decide: What does it practically look like to care for this temple that you’re living in every day? Keep this in your heart: my mind is a temple worthy of intentional care to live from a rooted place.

Today, as a simple practice, I encourage you to make note of a negative thought that typically comes up for you and write down at least two alternative ways to think about it. Sometimes just opening your mind to another option can help with perspective. It doesn’t mean that we’ll have perfect thinking, but it does mean that we can move through life differently and that there is real hope for getting better at renewing our minds.

Because in Christ, we’re no longer striving for worth but living from worth. Rest in that today.

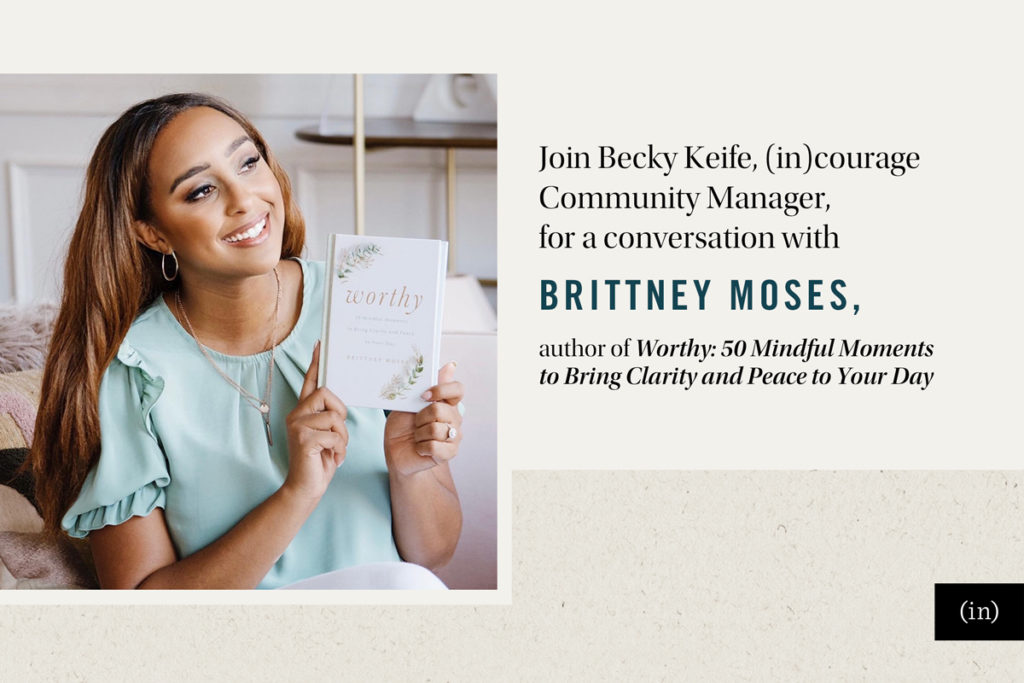

–This article is written by Brittney Moses. Brittney is a writer, speaker, advocate, and psychology graduate of UCLA who encourages the integration of faith, holistic mental health, and wellness. She hosts the Faith & Mental Wellness Podcast and loves hanging out at the beach with her husband and son.

—

Many of us are struggling at the intersection of our faith and our mind. We are bio-psycho-spiritual beings — body, mind, and soul. It all works together. If one is off, the others are off.

The fifty devotions by Brittney Moses in Worthy: 50 Mindful Moments to Bring Clarity and Peace to Your Day meet you at that intersection, helping you to mind the moments so your body, mind, soul balance stays in line. The resulting clarity and peace will overwhelm the doubt and insecurity that builds up from when we compare ourselves to others or hide our true selves. Through simplistic design, and short, yet impactful messages of peace and clarity, along with inspirational quotes and research-developed mental health trackers, you will be able to declutter your mind and focus on your personal wellness on a daily basis.

Whether you need a total digital detox or just a little more balance, Brittney Moses has gathered the information and inspiration to help you achieve your goals with Worthy, which releases next month. Preorder your copy today, and leave a comment below for a chance to WIN one of FIVE copies!

Then join Brittney and (in)courage community manager Becky Keife for a chat all about Worthy! Tune in tomorrow, 7/27/22, on our Facebook page for their conversation.

Giveaway open to US addresses only and closes on 7/29/22 at 11:59 p.m. CST.